By Craig Olsen, Originally published in the IAMC Newsletter, April, 2010

The science of riding a motorcycle is intrinsically linked to the art of safely identifying and managing risks. The more skilled we become in the proper techniques of riding by learning and practicing good riding habits, the more we can safely enjoy this sport. As we ride, we continually scan ahead (as well from side to side and behind us) to assess our riding conditions, identify potential risks (curve up ahead, oncoming traffic, entering side road, rock or rut in our path, deer or pedestrian at the side of the road, vehicle closely following us, etc.), and then appropriately respond by minimizing the risk or eliminating it when possible.

Regardless of how skilled we become as a rider, the universal element always working against us – incrementally impairing our ability to appropriately identify and manage risk – is fatigue. Fatigue is an umbrella term covering internal states and performance decrements associated with a need for sleep, tasks/environments that are mentally or physically demanding, and tasks/environments that are insufficiently stimulating. [1] For purposes of this discussion, fatigue has two components:

1. Sleepiness/drowsiness ‐ a propensity to fall asleep, have micro sleeps or make related task errors. It is caused by an acute or accumulative lack of adequate sleep, circadian effects, sleep disorders and various drugs or medications (alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, marijuana, antihistamines, etc.). Generally, there is a subjective state of sleepiness or drowsiness, but the rider may not be aware of how close he or she is to falling asleep and task errors may occur before the subjective state becomes apparent.

2. Excessive task demand (ETD) – a propensity for reduced performance caused by continued mental or physical effort at a demanding or prolonged task, or in an uncomfortable or hostile environment. It may be accompanied by a subjective state of exhaustion, weariness or physical discomfort, but performance decrements may occur before such states become apparent. We have internal physiologic clocks that regulate our body’s automatic functions including our sleep‐wakefulness cycle. Each is programmed with his or her own requirements and cycle times, and our internal clock tries to keep us on a “normal” 24 hour sleep rhythm synchronized to light‐dark (day‐night) cycles. [2]

Just traveling through different time zones shifts the internal clock forward or backward, temporarily disrupting the normal circadian rhythm. Accommodation generally takes one day for every time zone traversed.

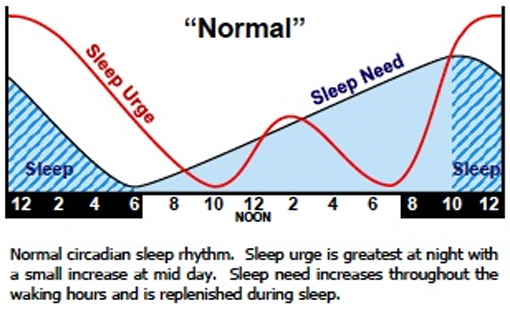

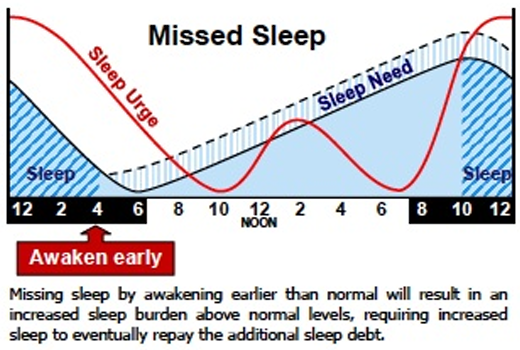

The sleep urge (circadian rhythm) has a normal bimodal distribution with the strongest need to sleep occurring between midnight and 6am and a second but small need occurring 2‐4pm, referred to as a rider’s “post‐lunch dip.” Corresponding to this, studies have shown a higher incidence of single vehicle motorcycle crashes occurring in the afternoon during the time period of 2‐4pm. It is generally considered that fatigue is more common in single‐vehicle crashes than multivehicle crashes. [3,4,6]

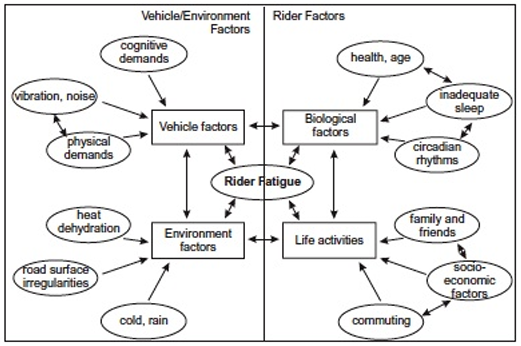

The factors contributing to rider fatigue are both environmental as well as intrinsic and are conceptually summarized in the following diagram. [3,6]

As the level of fatigue increases, the ability to identify risks and appropriately respond to them is delayed, characterized by slower decision making and longer reaction times. The greater the fatigue, the greater is the tendency to underestimate the amount of fatigue and the magnitude of the rider to sleep. This adds to the danger of unrecognized fatigue effects. At night, these effects are exacerbated as our darkened surroundings provide fewer clues to reality and we have less data with which to make proper decisions.

1.

Slower

reaction

times

‐

failing

to

slow

adequately

when

coming

into

a

sharp

corner

or

braking

too

hard

to

avoid

a

hazard.

2.

Reduced

awareness/vigilance

–

riding

slower

than

normal,

being

surprised

by

a

passing

car,

tailgating

or

not

seeing

deer

or

other

road

hazards.

3.

Impaired

decision making

–

not

stopping

to

rest

when

tired,

taking

an

inappropriate

route,

or

inability

to

choose

from

a

dinner

menu.

4.

Impaired

memory

–

passing

a

gas

stop

when

low

on

fuel,

forgetting

your

wallet

after

fueling

or

forgetting

to

make

an

important

telephone

call.

5.

Loss

of

situational

awareness

–

failing

to

recognize

a

stop

sign

or

signal,

failure

to

“go”

when

the

light

changes,

not

putting

the

kickstand

down

when

getting

off

the

bike,

failing

to

put

feet

down

when

stopping

or

stopping

in

high

gear.

6.

Performance

decrement

–

inability

to

calculate

purchase

amounts,

inability

to

formulate

routing

plans,

failing

to

communicate

with

riding

buddies

or

fixating

on

a

task.

Every rider will recognize having had one or more of these symptoms at one time or another during a ride. It is virtually impossible to completely avoid fatigue while riding, especially on multi‐day rides. The best way to handle fatigue – like any riding risk – is to appropriately identify it and minimize it. Since, as already discussed, many of the ill effects of mounting fatigue occur before the rider is aware of being fatigued, it is wise to have a riding plan that continually accounts for and minimizes fatigue. Here are several things a rider can do before, during and following a ride to minimize mounting fatigue. [1,2,3,5,6,7]

Adequate sleep/rest – It is imperative to get a good night’s sleep before a long ride and especially each night of a multiday ride. Make frequent stops at least every 90 minutes and no longer than every two hours during long rides to rest. Ideally, these rest periods should be at least 20 minutes long. A nap of 5 to 45 minutes, particularly during the “post‐lunch dip,” can be very refreshing and even life saving. Waking from a nap longer than 45 minutes but less than 2 hours can cause “sleep inertia,” a state of groggy disorientation that lasts 15‐20 minutes. On multiday trips, plan for extra rest every third or fourth day (either no riding or a markedly reduced amount of riding) to let your body and mind recover.

Realistic ride planning – Have everything done and your bike packed the evening before a long ride. You will sleep better that night. Plan enough flexibility into your trip, especially multiday ride trips, to account for weather and road changes that may delay you. Allow extra time for the above‐mentioned rest stops. Avoid riding when it is dark (late night or early morning). Do not ride beyond your ability. Take into account that the more challenging the ride, the more fatiguing it will be.

Ride comfort – Configure your bike to produce the least fatigue by eliminating those things that increase the work of riding or contribute to developing fatigue. A laminar flow windscreen that directs air up and over the rider will minimize a motorcycle’s aerodynamic drag and will sufficiently reduce wind pressure and deflect rain to considerably increase fatigue tolerance. A windscreen should not distort your vision. You should actually look over the windscreen, not through it. Your helmet screen or sunglasses should also not distort your vision. Earplugs significantly decrease the din of motor and exhaust noise, as well as road and wind noise, thus decreasing this stress that leads to fatigue. They also protect against hearing loss associated with exposure to constant environmental noise. A full‐face helmet cuts down more on ambient wind noise and wind buffeting than a half or three‐quarter face helmet. A comfortable seat and proper riding position will significantly cut down on muscular and body stress that contribute to fatigue. By having appropriate riding attire and layers a rider can adjust for and minimize the effects of extreme heat and cold that significantly contribute to the build up of fatigue.

Physical fitness and riding ability – Dual sport riding is a physically demanding sport, especially when riding demanding terrain. The better physical shape you are in, the better your body and mind will handle the fatigue caused by a demanding ride. The more comfortable you are riding challenging terrain, the less fatigue you will have riding it. Practice does make perfect. Learn good riding habits and techniques, and then practice them regularly. Practicing bad riding habits and techniques will not help you ride better nor will it lessen your fatigue. Since walking and performing mild exercise increases alertness, promotes blood flow and reduces stress in fatigued muscles, it is beneficial to do this during your riding breaks on long trips.

Nutrition and hydration – Maintaining adequate hydration is essential in staving off the effects of fatigue. Dehydration significantly decreases mental and physical function and dramatically accelerates and magnifies the effects of fatigue. Water and electrolyte solutions (Gatorade) are best when taken regularly during a ride through a hydrating system (Camelback or equivalent). While riding, smaller more frequent snacks may lessen fatigue better than a heavy meal especially just before the “post‐lunch dip.”

Caffeine – This is a controversial one. While some studies have shown a beneficial effect from caffeine (coffee and high energy drinks) in delaying the effects of sleepiness from fatigue, the best countermeasure for sleepiness is proper sleep. The effects of caffeine may delay the effects of sleepiness only temporarily, and when the caffeine effect wears off, the rebound sleepiness may be much more profound. If you use caffeine as your primary means of dealing with the fatigue of riding, you are living on the edge and need to rethink your fatigue management strategies.

Alcohol – In any form or amount alcohol is a depressant and therefore deteriorates both mental and physical function (judgment and reaction times). On multiday rides waking up in the morning with alcohol fatigue is not a good riding practice for the rider or the group.

Medications – Keep in mind that the side effect of some medications is drowsiness (such as antihistamines) and should be avoided when riding.

For more information refer to the following sources from which information for this article was obtained.

References:

1.

Horberry,

T.,

Hutchins,

R.,

and

Tong,

R.

(2008)

“Road

Saftely

Research

Report

No.

78

Motorcycle

Rider

Fatigue:

A

Review”

http://www.roadsafety.mccafusm.org/a/50.html

2.

Authur,

D.

(2005)

“Fatigue

and

Motorcycle

Touring”

http://ride4ever.org/news/fatigue.php

3.

Haworth,

N.,

and

Rowden,

P.

(2206)

“Fatigue

in

Motorcycle

Crashes.

Is

there

an

Issue?”

http://www.eprints.qut.edu.au/6247/1/6247_1.pdf

4.

Ma,

T.,

Williamson,

A.,

and

Friswell,

R.

(2003)

“A

Pilot

Study

of

Fatigue

on

Motorcycle

Day

Trips”

http://www.eprints.qut.edu.au/00006250/01/6250.pdf

5.

Gillen,

L.

(1998)

“Motorcycle

Rider

Fatigue

Survey

Results.

http://www.gillengineering.com/fatigue

paper.htm

6.

Haworth,

N.,

and

Rowden,

P.

(2006)

“Investigation

of

Fatigue

Related

Motorcycle

Crashes

–

Literature

Review

(RSD‐0261)

http://eprints.qut.edu.au/6250/

7.

Kitchen,

B.

“Fighting

Fatigue

on

Long

Motorcycle

Rides.”

http://www.suhog.com/sudnn/safetytip/tabid/73/default.aspx