by Craig O. Olsen, M.D.

Originally Published in the IAMC Newsletter, September 2016

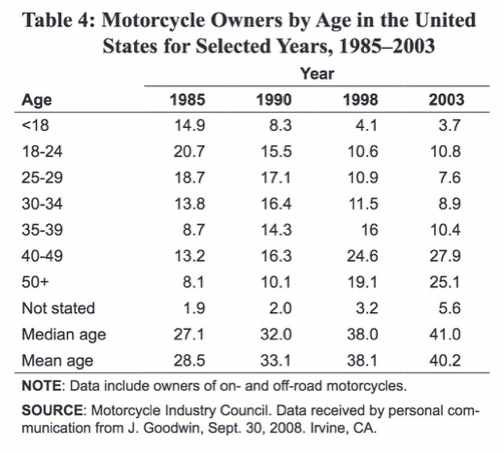

The first half of this story began six years ago when I wrote an article about the aging motorcyclist for our club newsletter. [1] Over the past decade, the mean age of motorcyclists has increased by 0.83 years per calendar year. The populaOon of motorcyclists is not only growing older, but the rate is increasing. The estimated mean age for 2016 is 58. [2-3] In 1985 the number of motorcyclists <25 years of age was 35.6% while those >40 years of age was only 14.5%. By 2003 those numbers had switched to 21.3% and 53.0% respectively.

Also of interest is that the number of females owning and riding motorcycles in the United States is increasing from 8% in 1998 to 14% in 2015. The majority of these women are younger from the Millennial Generation at 17.6% while women of the Baby Boomer Generation make up only 9% of female riders. [4]

An untoward consequence of the aging motorcycle ridership is summed by in the following 2010 statement from Science Daily: “Motorcycle riders across the country are growing older, and the impact of this trend is evident in emergency rooms daily. Doctors are finding that these aging road warriors are more likely to be injured or die as a result of a motorcycle mishap compared to their younger counterparts [1].”

These findings are not unique to the United States alone, but have been confirmed in other countries including, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and India to name a few. [1, 6-7]

There is nothing about the aging of motorcyclists that makes them immune to the inevitable deterioration of both physical and mental faculties experienced by the general population as it ages. At age 40 or 50 you may say that you will never stop riding, but at age 60 or 70 you might find that your priorities are changing. Five to fifteen years down the road (depending on your current age), there are realities to face, such as lengthened reaction time, poorer balance, fuzzier vision, and ongoing medical issues. As you age, your priorities will very likely be shifting from motorcycling to health. “Permission to ride tomorrow may be morphing from what you want to what your health will allow.” [2]

So, what is your plan to deal with the inevitable age-related changes in your riding abilities? Do you have an exit plan – a theoretical age at which you plan to quit riding? Or do you intend to continue riding for a few more years, modifying your riding tactics to accommodate your decreasing abilities? Whatever your plan, it would be wise to take steps now to help make it happen without too much anxiety. While we may not have a choice about growing older, we do have a choice about the quality of life; and the choices we make today help determine how our plan turns out.

Operation of a motorcycle requires visual and perceptual functions, cognitive and attention capabilities, and motor skill responses. Addressing these human functions, the Motorcycle Safety Foundation Rider Education and Training System (MSF RETS) has come up with the useful acronym of S.E.E., which means Search, Evaluate, and Execute. S.E.E. is a dynamic decision-making process with overlapping functions for maintaining a safety margin. A rider must search for potential problems, evaluate the level of risk, and execute a smooth, controlled response in avoiding or dealing with the problem. Following are some specific effects and recommendations related to aging riders: [8]

Search

1. Visual clarity diminishes with age, typically beginning gradually between the ages of 40-50 and declining modestly beyond age 60.

2. Night vision especially diminishes with age – an older person on average requires four times more light to see at night than a younger person.

3. Peripheral vision also diminishes with age.

4. Aging eyes are more sensitive to light, making it more difficult to adjust to light sources such as

responding to the glare of oncoming headlights.

5. Aging eyes take longer to adjust from near to far objects and vice versa.

6. With age eyes take longer to adjust to the dark.

7. Depth perception diminishes with age and may affect judging appropriate gap selection when

passing another vehicle and when crossing or turning at an intersection.

8. Hearing diminishes with age – 20% of people age 55 and 30% of those over age 65 are hearing

impaired.

9. With age street and directional signs are more difficult to read potentially increasing the chance

of input overload that occurs when there is more going on in traffic than may be accurately perceived or processed.

Evaluate

1. Aging riders are more likely to be on medications that may affect performance and behavior. Labels should always be read and a medical doctor’s advice should be followed.

2. Older riders often need more time to process information, and this becomes an increasing problem when a rider must contend with several points of information simultaneously, especially in unfamiliar areas and where complicated signage may be confusing.

3. Aging riders misjudge space and distance more frequently.

4.Awareness of impending risk is delayed in older riders.

5. Riding accidents are typically caused by the interacOon of factors. The number of road and traffic factors a rider may handle at any given moment varies, but aging may lower the number of simultaneous risk factors that a rider may be able to respond to safely.

Execute

1. Muscles weaken with age. Muscle tome and strength can deteriorate as a rider ages. Without weight training a person loses 6-10% muscle mass per decade starting at age 30.

2.

Endurance ocen diminishes with age. Oxygen is not utilized as efficiently and muscles lose their elasticity.

3. ReacOon Ome slows with age. Reacting to a hazard may take twice as long for a rider who has moved into middle age (40-54 years of age) and up to three to four times longer acer age 55.

4. Control sensiOvity lessens with age. The feeling of the road through the Ores and handlebars lessons, as well as the feedback that occurs in cornering and braking. This may have more serious implications for the aging rider in emergency maneuvers to avoid a crash.

Older riders ocen need more Ome to process informaOon, and this becomes an increasing problem when a rider must contend with several points of informaOon simultaneously, especially in unfamiliar areas and where complicated signage may be confusing.

Aging riders misjudge space and distance more frequently.

Awareness of impending risk is delayed in older riders.

Riding accidents are typically caused by the interactoon of factors. The number of road and traffic factors a rider may handle at any given moment varies, but aging may lower the number of simultaneous risk factors that a rider may be able to respond to safely.

Muscles weaken with age. Muscle tome and strength can deteriorate as a rider ages. Without weight training a person loses 6-10% muscle mass per decade starting at age 30.

Endurance often diminishes with age. Oxygen is not utilized as efficiently and muscles lose

their elasticity.

Reaction time slows with age. Reacting to a hazard may take twice as long for a rider who has moved into middle age (40-54 years of age) and up to three to four times longer acer age 55. Control sensitivity lessens with age. The feeling of the road through the Ores and handlebars lessons, as well as the feedback that occurs in cornering and braking. This may have more serious implications for the aging rider in emergency maneuvers to avoid a crash.

Recommendations – While these considerations should be taken into account by all motorcyclists, they are parOcularly valuable for riders reaching their mature years.

Riding Tips

1. Keep a greater following distance – perhaps three seconds or more. Some authorities recommend up to a six-second interval.

- Avoid complicated and congested roads and intersections. “Input overload” is a phrase often used to describe the presence of too much information to be able to process accurately. Pick a route that contains less complicated roadways with less traffic flow and fewer turns.

- Allow larger gaps when moving into a stream of traffic, and select a safe gap when passing another vehicle or crossing or turning at an intersection.

- Make a point to check side-to-side at intersections. Take an extra moment to double-check cross traffic to get a good look.

- Keep making good blind-spot checks. Traffic research shows that older drivers don’t check blind spots as well as younger drivers.

- Keep windshield, helmet face shield, and eyeglass lenses clean. Dirt and grime on a rider’s “window to the world” may adversely affect quick and accurate perception of traffic or road problems.

- Avoid tinted lenses at night. Any tint lessens the light available to the eyes and makes seeing well at night more difficult.

- Wear sunglasses when daytime glare is a problem. Good polarized sunglasses may reduce the effects of glare significantly and make idenOfying a traffic hazard easier.

- Adjust mirrors to avoid glare from following vehicles.

- Avoid classes with wide frames or heavy temples that may create a blind spot.

- Avoid being in a hurry. Leaving a little early will result in a more relaxed, enjoyable ride and

create an opportunity for choosing greater time and space safety margins. - Remember the average age of the driving population is increasing, and you are sharing the road with others who may be experiencing the effects of aging on their operation of a motor vehicle.

By 2020, it is estimated there will be more than 30 million licensed drivers age 70-plus.

Motorcycle Choice

1. Choose a motorcycle with large dials and easy-to-read symbols. Brightly illuminated gauges may be helpful for riding at night.

2. Choose a motorcycle that fits well and does not cause muscle strain because of an unusual seating position or because the controls are difficult to operate.

Personal Responsibility

1. Wear protective gear all the time. Using extra body armor may help mitigate injury should a fall occur.

2. Renew skills often by completing a MSF or STAR riding course. The half-day of practice is fun and helps keep riding skills fresh.

3. Separate alcohol and other impairing substances and conditions from riding. Over-the-counter and prescription medications may cause impairment, as well as the possible synergistic impairment when drugs are used in combination.

Taking care of your health as you age may facilitate your ability to ride longer into the sunset of your life. It is never to late to start nor too early to begin thinking about and taking positive steps to improve and maintain a healthy lifestyle. The two most significant factors in this regard are diet and exercise. Your life expectancy is inversely proportional to your weight. Overweight and obesity are strongly linked to type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, stroke, certain types of cancer (colon, esophagus, pancreas, kidney, uterus, breast and prostate), dyslipidemia (high cholesterol and triglyceride levels), liver and gallbladder disease, sleep apnea and respiratory problems, osteoarthirits (degenerative changes in joint, cartilage, and underlying bone) and gynecological problems (abnormal menses and infertility). Weight reduction significantly reduces the risks associated with as well as developing all of these disorders. [9]

The sad truth is that while we have an abundance of food in the U.S., nutritional value seems to have become a very low priority. More and more American food is highly processed and overloaded with carbohydrates, corn syrup, salt, unhealthy fats and questionable chemicals. eating out (or brining home ready-to-eat meals) is so cheap and easy in the U.S. that it seems normal to order what looks good in the menu pictures, and gobble it down without any concerns for nutrition, portion sizes, or questionable additives. [10]

There are lots of sources to access on healthier eating with books available, a seemingly unending supply of online articles, and medical websites where you can search detailed information about health issues free of charge. [9-10] If you are confused or have difficulty, ask your primary care physician to refer you to a dietician for some professional guidance.

Exercise coupled with healthier nutrition has a synergistic effect in reducing weight and improving overall health. Research shows that exercise helps curb food cravings, increases energy, improves memory, and reduces the risk of certain cancers. For many finding time to exercise on a regular basis is a major problem. In that regard I like the physician’s response to the patient in the cartoon to the left, “What fits your busy schedule be]er, exercising one hour a day or being dead 24 hours a day?” Exercise can and will improve your health and insure that you are able to continue riding well into your golden years.

Of the four components of physical fitness (defined as flexibility, strength, endurance and balance) strength is the easiest and quickest to develop. Strength building involves resistance exercises (using free weights, resistance machines, or the weight of your body). If you are out of shape and start doing regular resistance exercises, you may expect to see a 50 percent increase in your strength in less than a month. While it is possible to develop your strength from resistance exercises using commercial or home gym equipment, you can also accomplish it at home with very minimal equipment and expense. There are numerous sources for exercise programs focusing on the four components of physical fitness that you can do at home or at a gym. [10-12] The important thing is simply to begin and stick with it.

Remember, it is never to late to start nor too early to begin taking posiOve steps to improve and maintain a healthy lifestyle. The two most significant factors in this regard are diet and exercise. May the second half of your story be a healthy one that enables you to ride well into the sunset of your years.

References:

- “The Aging Motorcyclist,” by Craig O. Olsen, M.D.; IAMC Newsletter, Issue 5, December 2010. hYp://

motoidaho.org/sites/default/files/IAMC%20NewsleYer%20(12-2010%20issue%205)_0.pdf - “The Rest of the Ride – Part 1: Growing Older,” by David L. Hough; Motorcycle Consumer News, August 2016;

47:32-33. - “Motorcycle Trends in the United States,” by C. Craig Morris; Bureau of Transportation Statistics Special

Report, May 2009. hYp://www.rita.dot.gov/bts/sites/rita.dot.gov.bts/files/publicaOons/

special_reports_and_issue_briefs/special_report/2009_05_14/pdf/enOre.pdf - “U.S. Female Motorcycle Ownership Reaches All-Time High,” by Jensen Beeler; Asphalt and Rubber, 18

December 2015. hYp://www.asphaltandrubber.com/news/female-riders-usa-stats/ - “Motorcycle Fatality Facts,” Insurance Institute for Highway Safety & Highway Loss Data Institute, 2014.

hYp://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/motorcycles/fatalityfacts/motorcycles/2014#Age-and-gender - “Rise in injury rates for older male motorcyclists: An emerging medical and public concern,” by Mariana

Brussoni. et al., BC Medical Journal, October 2014; 58:386-390. hYp://www.bcmj.org/sites/default/files/

BCMJ_56_Vol8_motorcycle.pdf - “Motorcyclists 2014,” Ministry of Transportation, New Zealand Government, 2014. hYp://

www.transport.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Research/Documents/Motorcycles-2014.pdf - “Seasoned Rider Fact Sheet,” Motorcycle Safety Foundation Rider Education and Training System. hYp://

www.msf-usa.org/Digital.aspx#eCourse and hYps://www.motorcycletrainingacademy.com/docs/

X_SeasonedRider_Fact_Sheet.pdf - “Why Does my Riding Gear Keep Shrinking?” by Craig O. Olsen, M.D.; IAMC Newsletter, Issue 3, June 2011.

hYp://motoidaho.org/sites/default/files/IAMC%20NewsleYer%20(6-2011%20Issue%203).pdf - “The Rest of the Ride – Part 2: Food and Exercise,” by David L. Hough; Motorcycle Consumer News,

September 2016; 47:40-41. - “Geong in Riding Shape,” by Craig O. Olsen, M.D., IAMC Newsletter, Issue 1, February 2013. hYp://

motoidaho.org/sites/default/files/IAMC%20NewsleYer%20(February%202013%20-%20Issue%201).pdf - “The FREE 45 Day Beginner [Exercise] Program,” by Stew Smith, former Navy SEAL and a Certified Strength

and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS). hYp://www.stewsmith.com/ and hYp://site.stewsmithptclub.com/ 45dayplan.pdf